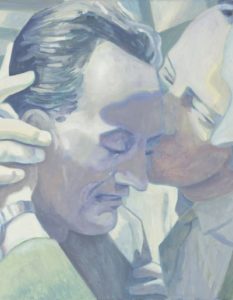

The emotional dimension of these reflections and its depiction in works of art can also be applied to the tragedies caused by sudden and unpredictable events, such as natural disasters, accidents or terrorist attacks. The series by Vanriet presented here refers to an airplane crash and confronts us directly with the mourning of the victims’ close relatives, whose serene despair is tangible in the faces of the characters portrayed.

Artists have often been inspired by the terrible plague epidemics that have reoccurred throughout history. The Black Death, which was responsible for the death of more than half of Europe’s population around the middle of the 14th century —and was even more destructive than the one that ravished the Byzantine Empire under the Justinian dynasty—, profoundly inspired a number of creators as well as artistic and literary topics such as The Triumph of Death and Dance of Death. Nicolas Poussin, the great master of French classicism, was undoubtedly thinking of the terrible Milan epidemic of 1630 when he painted, over the course of that year and the following year, The Plague of Azoth, which illustrates a biblical passage using a composition with Raphael roots.

Goya left us an impressive image of the conditions that patients had to endure in hospitals at the time; his small painting entitled Plague Hospital (1798–1800) resembles his prison scenes, equally claustrophobic and producing the same feeling of abandonment, indiscriminate overcrowding, and impending death. Shortly after came the declamatory work of Bonapartist propaganda, Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa by Antoine-Jean Gros, the disciple of David who played a great role in the creation of the Napoleonic legend. It depicts an episode that supposedly occurred during the Egyptian campaign in 1799 and shows Bonaparte visiting the hospital where the infected French soldiers were secluded; having taken off his gloves, he undauntedly touches the bubo of one of the victims with a gesture resembling the “royal touch” of the kings of France —and later the kings of England—, with which they cured scrofula, according to tradition. The painting dates from 1804, the same year that General Bonaparte was crowned emperor, coinciding with his potential desire to attribute himself with the monarchs’ thaumaturgical powers.

In our times, AIDS came to remind us of our vulnerability and of the omnipresence of threats. It generated a more committed attitude from artists than what had been seen since the sixties; exhibitions were celebrated in various countries, represented in the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2013, which recalled that Ronald Reagan, president of the United States at the time that the pandemic was declared, failed to mention the name of the disease publicly for six years, therefore failing to recognize its existence and severity. Many creators saw art as a driver of social change as well as an expression of life and made an effort to avoid the stigmatisation of certain groups, such as the gay community. Some actions of solidarity stood out, like the transport of Pepe Espaliù, who was carried in Madrid by a couple of volunteers in 1992, shortly before his death. However, AIDS revealed that developed societies only react and take necessary action when they are directly affected by an extreme situation. In the face of present and future threats, it is worth remembering that the world, with or without globalization, belongs to everyone and that all lives are equal.

Jan Vanriet was born in Antwerp, Belgium. He studied at the city’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts and combined painting and poetry. In 1968, he participated in protest actions of writers against literary censorship in Belgium. In 1972, he presented his first exhibition at the Zwarte Panter gallery and later started his collaboration with the gallerist Jan Lens (Lens Fine Arts). His books, published by Manteau, literary collaborations and magazine-cover designs for the literary magazine Revolver were alternated with his exhibitions: biennials in Sao Paulo, Venice and Seoul as well as Galerie Isy Brachot in Brussels and Paris (1982), amongst others. In Antwerp, as the European Capital of Culture in 1993, he organised an important exhibition and painted the lounge ceiling of the restored Bourla Theatre. The Lippisches Landes museum (Detmold) presented his exhibition Transport (1994–2004), a series of paintings inspired in part by the Second World War: his parents and other members of his family took part in the Resistance against the Nazi invaders, but they were arrested and deported to concentration camps in Mauthausen and Ravensbrück.

In 2005, Vanriet travelled to Israel to install his triptych Nathan the Wise. In 2010, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Antwerp invited him to “close” the museum before its renovation and organised the retrospective Closing Time in dialogue with classic and modern artists, such as Rubens, Van Eyck, Tiziano, Cranach, Memling, Fra Angelico, David, Mellery, Rouault, Modigliani, Corinth, Van de Woestyne, Ensor, Léonard, Servranckx, Peeters, Van de Berghe, Spillaert, Nicholson, Permeke, Alechinsky and others. In 2012, the Roberto Polo Gallery in Brussels inaugurated with Closed Doors, his first solo exhibition there. In 2013, he presented Losing Face, a series about Jewish deportees from Belgium to Auschwitz, which was shown at the Kazerne Dossin Museum in Mechlen and then at the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre in Moscow. Some of his works are conserved in the permanent collections of the National Museum in Gdansk, the British Museum, the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw and The New Art Gallery Walsall.

This is how Vanriet describes the series presented here: “Most of my work is related to memory and ‘collective mourning’, the overwhelming feeling of finding comfort within the community. Like English author Andrew Graham-Dixon wrote in relation to my themes: ‘Respect those who have suffered. Remember their wounds. In this act of remembering, make their wounds bleed again.’ Although my painting is about solidarity, that mutual support within a group, many of the people represented are simple individuals; they appear to be living in mental isolation. I do not think it is out of despair. I suppose that they are searching for their identity. They are asking themselves who they are. Confused, they realise that modern society hardly creates fundamental stories anymore, and even those great stories have suddenly vanished. They are aware that their paradise has been severely affected. They ask themselves: Who can explain this? How did it happen? Where did it go wrong? I started creating one of my recent oil paintings (Embrace, Coffin) after the opening of the museum Colección Roberto Polo, visiting Toledo, admiring some of El Greco’s masterpieces. I was impressed by the real power of art: how we are still inspired today by the pain and comfort painted many centuries ago,” he concluded.

Like Goya or Gros, Jan Vanriet does not remain indifferent in the face of misfortune and he joins that list of artists who transcend trends with determination. In the late 1980s, the combination of a series of political, social and economic factors fostered, as mentioned earlier, a major shift in many artists’ sensibilities and in the focus of art creation. Following the speculative euphoria of the last two decades, COVID-19 hits us in this bitter-cold period and reminds us, like vanitas, of the emptiness of life and the relevance of death as the end of worldly pleasures. Our lives have been put on hold, confined behind a balcony or window, from which we contemplate about utter desolation, as if we were characters from a painting by Edward Hopper.

Rafael Sierra

Artistic Director

Colección Roberto Polo. Centro de Arte Moderno y Contemporáneo de Castilla-La Mancha